Two centuries ago, a tale of absolute horror emerged from the transatlantic slave trade. The French ship Le Rȏdeur (‘The Prowler’) was a 200-ton cargo vessel that left Le Havre on 24 January 1819 bound for West Africa under the command of a Captain Boucher. She anchored at the island town of Bonny on the Calabar River in modern Nigeria, West Africa, and arrived back in Le Havre on 22 October 1819. It was during this 10-month journey that a mysterious eye affliction had rendered almost the entire crew and cargo blind, leading to the murder of 39 African slaves who were mostly thrown overboard as ‘damaged goods’ unsaleable in the Caribbean markets.

Trading in slaves had been illegal in France since 1818. For some years, the British Royal Navy had maintained a dedicated anti-slaving force known as the West Africa Squadron. Their job was to patrol the waters in the region and interrupt trading activity, and across its 50-year history, more than 150,000 slaves were released from captivity. The activities of the squadron and the status of the wider international slave trade were compiled each year into annual report presented to the British parliament by a Select Committee.

According to the Report of 1821, there was an initial enquiry undertaken by Baron Pasquier, the French Minister for Foreign Affairs, who extracted a statement from Captain Boucher who claimed that he had encountered Spanish and Portuguese slave ships in the Calabar River whose practice it was to assume the names of ‘innocent’ ships they passed by. In effect, Boucher was pleading mistaken identity, an argument swept aside by the British as “obviously false”. The Committee were also in possession of a French investigation made by the Bibliotheque Ophtalmologique in Paris, and it too was repeatedly criticised as being little more than a cover-up.

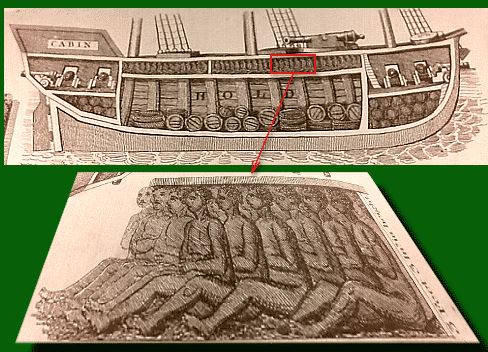

Calabar was a magnet for slaver traders, and since 1807 British warships had actively pursued slave ships in and around the region, Britain having abolished slave trading in that year. Le Rȏdeur had arrived at Bonny on 14 March, and the crew of 22 enjoyed shore leave for the next three weeks. At no point in this period was eye disease or any other illness observed within the crew. However, 15 days into the voyage across the Atlantic, the cargo of nearly 200 negro captives “had contracted a considerable redness of the eyes that spread with singular rapidity” , almost certainly a virulent form of conjunctivitis, rendering many of them completely or partially blind. At first this was put down to the fetid air below decks, or even the paltry water rations, by then down to a small glass each day for each person. According to the French report, the slaves were brought up on deck “in order that they might breathe a purer air”, but many became afflicted with Nostalgia (then considered to be a specific ailment of the mind) and threw themselves into the sea “locked in each other’s arms”, ‘compelling’ Captain Boucher to again chain up the rest below decks.

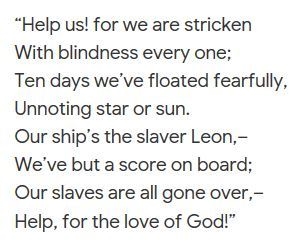

Within a matter of days the whole crew except one man was struck down with the disease, which often accompanied severe dysentery possibly caused by them drinking rainwater to assuage their raging thirst. Perhaps some blamed their earlier encounter on the open seas with the Spanish ship Leon whose crew had also been blinded by an eye contagion. The Spaniards begged to be taken on board Le Rȏdeur, but they were refused, mainly because of the lack of provisions. The Leon was never heard of again.

The Rȏdeur reached Guadeloupe on 21 June, “her crew being in a most deplorable condition.” Twelve were entirely blind, one of whom was the ship’s surgeon; five had lost one eye, and one of them was the captain; and four more were partially injured. The one man who had remained unaffected was struck down three days after their arrival in port. According to the British investigation, 39 slaves were said to have been completely and permanently blinded, and these had been thrown into the sea by Boucher and his crew. The French report insisted that they had voluntarily drowned themselves because they were homesick. A total of 160 slaves were eventually landed ashore and driven by whips to the markets.

While not doubting the verifiable facts of the voyage itself – dates, destinations etc – the British committee thoroughly condemned the findings of the French investigation, especially when it praised Boucher for “lavishing his attention” on the slaves and his crew “with a zeal and devotedness that exceeds all praise.” The British government had received a copy of a witness statement made by a Monsieur Morenas to the French Chamber of Deputies in June 1820 in which he claimed that the 39 blind slaves (some sources say 36) had been thrown into the sea because they were now valueless and not worth the expense of feeding them. Further research revealed that an insurance claim had been paid in regard to the 39 lost slaves who, according to the agents, were the weakest of the cargo and sacrificed due to the lack of water on board. A sickening twist was added when Le Rȏdeur received a second slave transport commission the following year, sailing again from Le Havre and again under Boucher because of his ‘devotion’ shown in the earlier voyage.

The British report concluded that the case of the Rȏdeur presented “a striking proof of the impunity with which the most open and notorious contraventions of the Abolition Laws may be committed in France”, adding that “not one effectual step” had been taken to bring the perpetrators of the crime to justice; in fact wholesale neglect, murder and insurance fraud had been rewarded with further commissions and all involved continued to enjoy “the fruit of their illicit commerce, and to devise and perpetrate fresh outrages against the natives of Africa.”

This stinging condemnation called for the French government once again to intervene and examine the testimonies of the crew, including the surgeon Monsieur Maignan, who were known to be still residing in France. Another earlier official review by the French Minister of Marine in December 1819 had completely exonerated Boucher – in fact, it found that he had been grossly slandered – and believed his story of ‘mistaken identity’, but this was derided by the British committee as a “well arranged system designed to conceal the truth and protect delinquents.” Paragraph after paragraph of the Report lambasts the French government for failing to recognise and act upon the overwhelming evidence of the illegality of the affair, especially when the ship and crew returned to Le Havre so obviously stricken and seeking medical help.

The whole ghastly business of the Rȏdeur gave the British government a glorious opportunity to take the moral high ground over the newly–restored French monarchy without quite apportioning actual responsibility to Louis XVIII and his ministers. Rather, the British took the view that some collusion had taken place at senior levels but stopped short at His Majesty’s council of ministers. A subsequent Annual Report on the Slave Trade (1822) took pains to clarify the British position by stating:

A nation cannot be charged with the crimes of a few individuals. Slave dealers belong to no country, and to unmask the captains of slave ships is not to impute blame to France.

In short, it was not worth the lives or the miseries of thousands of trafficked humans to risk a major diplomatic rupture between the two nations. It would be another eleven years before Britain abolished slavery in its entirety in 1833, followed by France some years later in 1848. The story of Le Rȏdeur was captured in poetic form by John Greenleaf-Whittier in The Slave Ships, an excerpt of which appears here.

Useful sources:

The Foreign Slave Trade: Report to the British House of Commons (1821)

Annual Report (1822) by the African Institution, London, England.

The West Africa Squadron: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Africa_Squadron

Carl Plasa: Doing the Slave Trade in Different Voices: Poetics and Politics in Robert Hayden’s First “Middle Passage” (African American Review, Vol.45 Winter 2012)

John Greenleaf-Whittier: The Slave-Ships (1834) Available at: https://www.bartleby.com/372/232.html

See also the artwork of Lubaina Himid at: www.historytoday.com/history-matters/lubaina-himid-naming-un-named

Title image: Depiction of a similar event from 1781 known as The Zong Massacre.

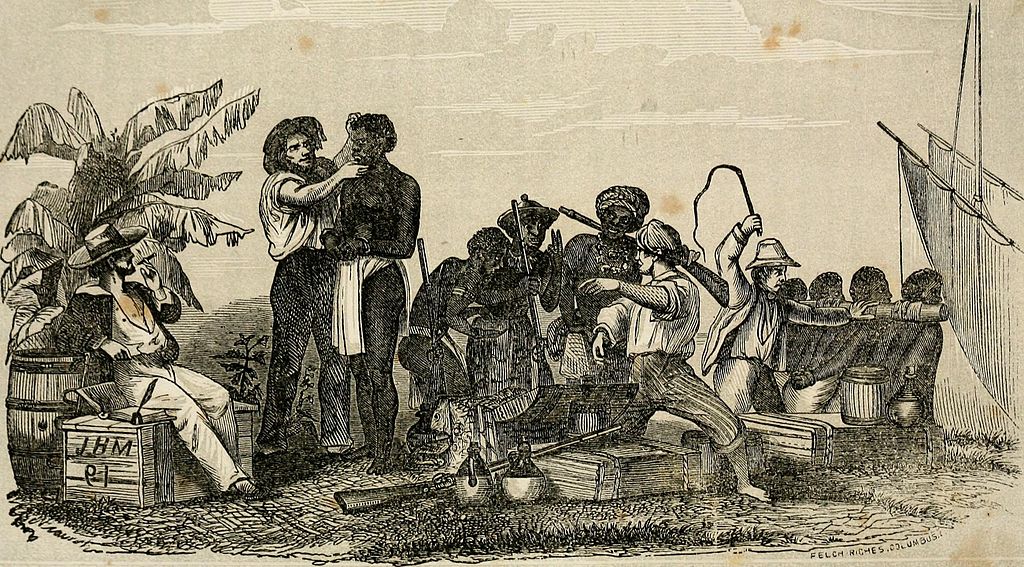

This unnerving image was produced by Isaac Cruikshank in 1792 to draw public attention to another travesty of justice regarding the treatment of slaves by British traders. Captain John Kimber of the merchant ship Recovery had been accused of the assault and murder of a teenage slave girl who had refused to dance on deck, an activity considered to be beneficial exercise. After repeatedly flogging the girl, Kimber had her suspended by one ankle and dropped to the deck several times. Five days after this torture, she died of her injuries. Kimber was tried by an Admiralty Court and ‘honourably’ acquitted of all charges. Within days, Cruikshank had produced the prints to demonstrate to the public the realities of slavery.

‘Tell us how your great-great-great-great-grand father being a slave has caused you to suffer’

How long have you got, Erik?

LikeLike

The barbarity of the transatlantic slave trade eternally condemns all who partook in it. The British Slave Naval Squadron only rescued less than 6 per cent of natives that were kidnapped and was motivated by prize money. Reparations to the Descendents of those slaves is long overdue. H.G. Wells intimated that the slaughter if the Europeans in the First World War was partial retribution for their atrocities.

LikeLike

Reparations…..why? Considering nobody on either side of this tragedy, slave or slaver, is alive, what’s the point? Who pays? Who receives payment? How much would they receive? Reparations were paid by Germany to Jews held in the concentration camps and America to the Japanese in their internment camps after World War ll, but that made sense since they were paid to those who actually suffered. Tell us how your great-great-great-great-grand father being a slave has caused you to suffer.

LikeLike