With thanks to Dr Edith Lister

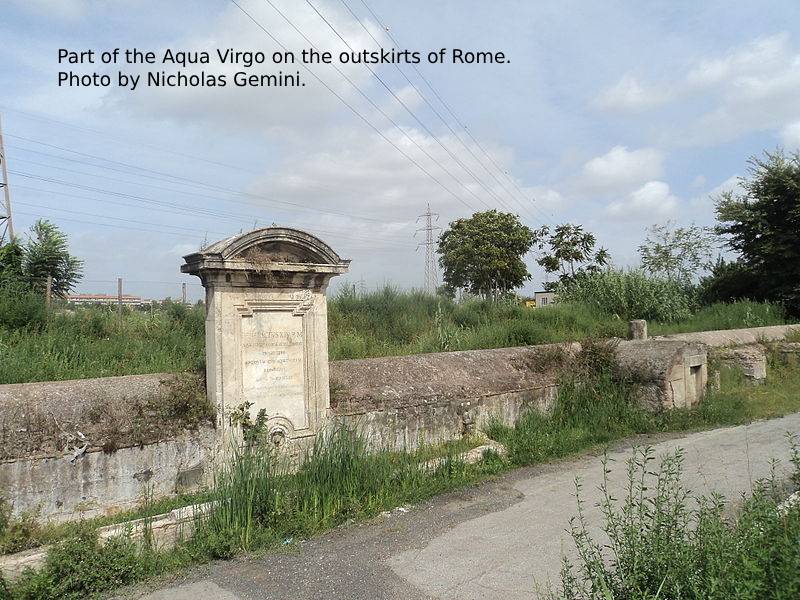

In the late 1990s, building work in the heart of Rome brought to light some fascinating ancient ruins. Known today as the Vicus Caprarius (*), the complex lies ten metres underground only a few yards from the world-famous Trevi Fountain. Opened to the public in 2004, the site contains two major constructions: the remnants of the Aqua Virgo, the last functioning aqueduct from ancient times; and the foundations of a luxurious town house built on three levels, now buried under sixteen centuries of development above.

Built by Marcus Agrippa, best friend and right-hand man of Rome’s first emperor Augustus, the Aqua Virgo (apparently named for the purity of its water) originates some 20 kilometres from Rome and was formally opened in 19 BC. Today, some of the aqueduct’s water goes to replenish the Trevi Fountain, but in antiquity it was used to fill the city’s cisterns and baths. Also, by virtue of some clever plumbing, a portion of the output was drained off to supply a lavish water feature in the town house. Visitors today can still see and hear the constant trickle of crystal clear water through 2000-year old pipework.

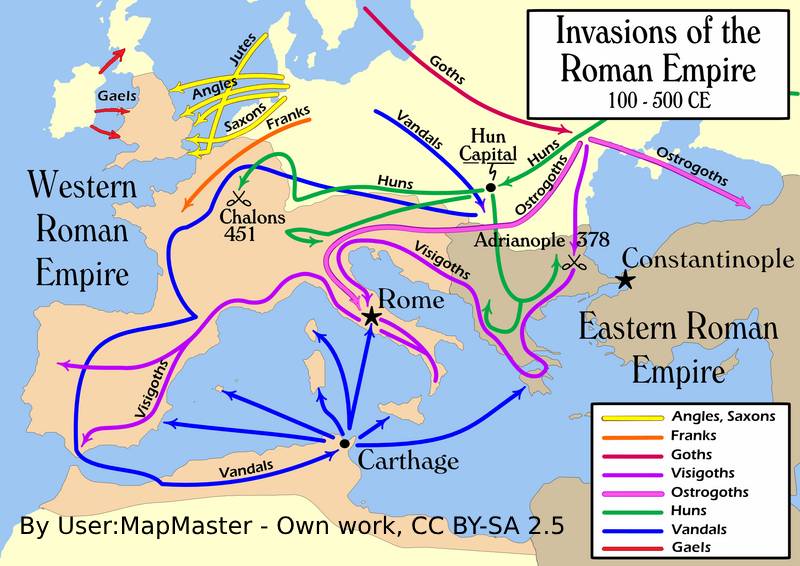

The former owners of the town house are unknown, but excavations indicate that it was devastated by fire, most probably during the Sack of Rome by the Vandals in 455 AD, judging by the issue dates of coins found in the house. This was a time of immense social and political stress which historians have called the Migration Period. All across Europe, entire tribes were on the move exploiting the impending collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

Among the many artefacts discovered in the ruins was a cache of 873 coins wrapped in cloth and hidden in a cheap pottery jar. Examination of these coins show that they are low-denomination nummi made of copper and bronze, with issue dates ranging from Claudius (41 to 54 AD) through to Valentinian III (425 to 455 AD.) It was not uncommon for old copper coins to circulate for centuries during the Roman empire, such was their low worth and limited propaganda value.

The total buying power of the cache was very low indeed. Ancient monetary values are notoriously difficult to estimate, sometimes impossible, but it would seem that a single nummus represented 1/7200th of a gold solidus. If we then consider the average pay for a Roman soldier in Late Antiquity, we find that he received roughly two to three solidi a year plus numerous other benefits in kind such as his food and board. A single solidus weighed 4.5 grams, roughly £220 ($280) at today’s gold prices, and this gives us an approximate value of £27 ($34) for the entire hoard (220/7200 x 873.)

But whose money was it? The cache was found in the servants’ area of the house, so it seems likely that it belonged to a slave or a free employee. Perhaps he or she was eagle-eyed and picked up coins from the streets when sent on errands. Perhaps it was leftover pay, squirreled away over many years, every so often a nummus dropped in the jar as we might have a coin bank today. It could literally have been the life savings of a person, age unknown, but who hoped one day to provide a dowry for a daughter, buy a new outfit, have a day off, pay for medical care or even to escape the city at a time when soldiers filled the streets and people had spoken of decline and fall for decades. We will never know either the owner or the purpose, but the Servant’s Hoard gives us a glimpse into that aspect of Roman history so easily overlooked or forgotten – the lives of the poor.

Copper and bronze coins of Valentinian III, typical of the nummi found in the hoard.

Vicus Caprarius – L’Area archeologica sotterranea alla Fontana di Trevi

(*) Curiously, the name Vicus Caprarius translates to ‘goat village’, but the Rome Tourist Authorities prefer to call the site ‘The City of Water’.